Have you ever wondered how to figure out your exact maintenance calories? If so, it can seem like a complicated process and if you feel that way…

You’re not alone.

There are tons of maintenance calorie calculators and fancy equations out there. And while they can be helpful, you don’t have to spend a ton of time on this idea if you just want a starting point for the number of calories you should be eating daily.

In this article, you’ll learn exactly how to determine your maintenance calories (and more).

What are your so-called ‘maintenance calories‘ exactly?

Here’s a simple definition:

Maintenance calories are the total amount of calories required on a daily basis to maintain your body weight with no gains or losses in fat and/or muscle tissue.

The human body requires energy every day to maintain bodily functions and to regulate body weight.

The food you eat everyday (your daily calorie intake) is used in various ways to repair your muscles after hard workouts, and help your cells turnover to create new ones.

And your daily calorie intake is either stored as fat, or stored as glycogen (carbs) into your muscles.

Both of these processes provide energy to your body for regular movement and exercise and the manipulation of calories will eventually alter your body composition.

Maintenance Calorie Intake

To calculate maintenance calories, you need to understand calorie balance first.

If you’re not gaining or losing weight at your current caloric intake, this is what we refer to as your maintenance caloric intake.

To ‘maintain’ your current weight simply means that you’re constantly replacing the energy you’ve burned with energy from the food you eat.

It’s a cyclical process and you’ve been doing it your entire life without ever thinking about the concept of maintenance calories or some specific number of daily calories before.

Struggling With Weight Loss?

Learn My Tricks & Tips to Make Weight Loss Easier

(it’s actually quite simple, and I can help)

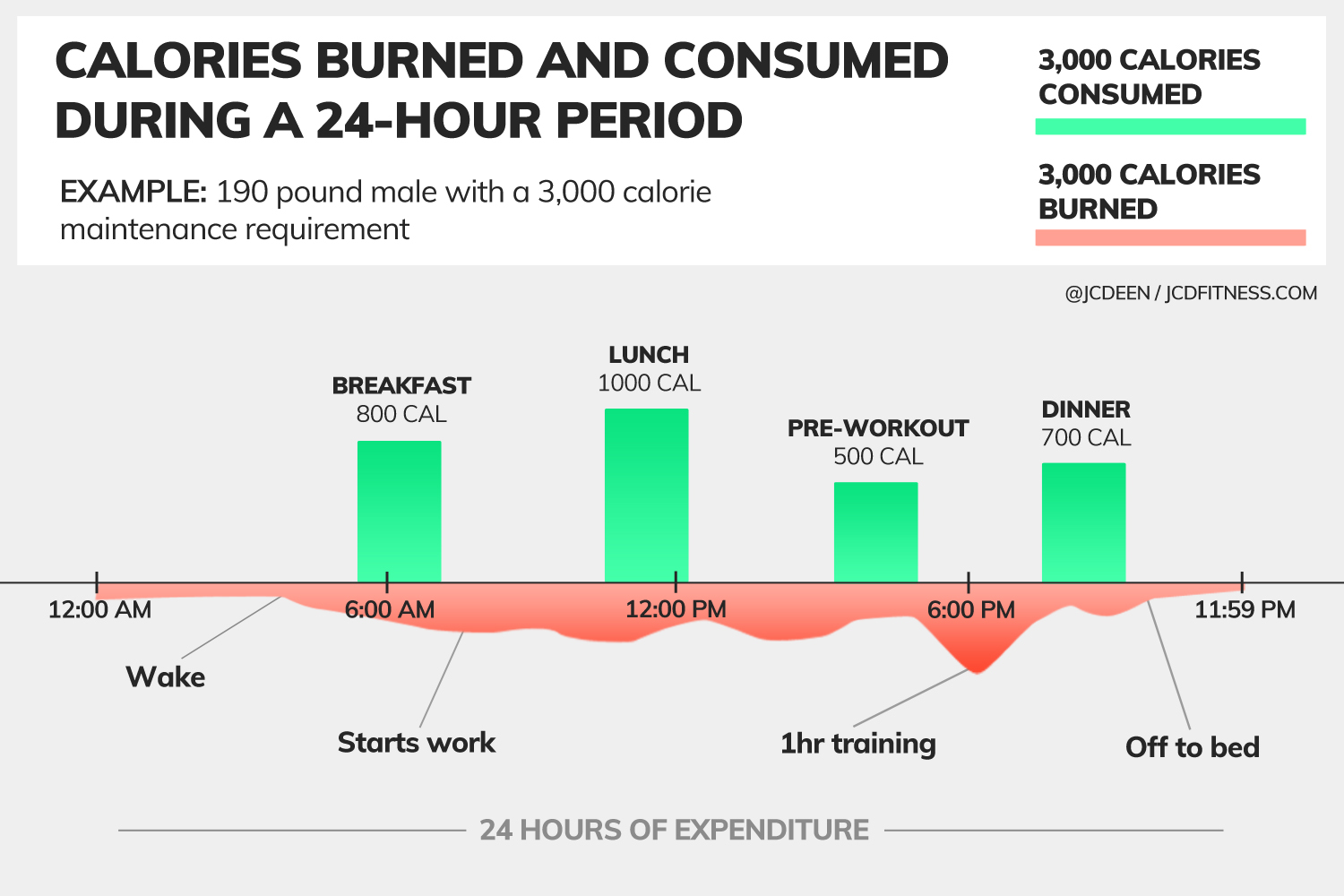

I’ve illustrated how this works in a chart below:

Understanding your expenditure over a 24-hour period

As you’ll see, if you burn 3,000 calories over a 24-hour period (daily physical activity included), and you consume 3,000 calories, then you’ll not gain or lose weight.*

You’ll maintain your body weight with no fat and/or muscle gain or loss.

*Note: your weight can (and will) fluctuate over time, usually within 1-5 pounds. It could fluctuate more depending on various factors like glycogen storage, water retention, bowel movements, urination, sodium intake, and more.

So you’re hardly ever going to see the same exact weight on the scale every day.

Just here for the maintenance calorie calculator? Access the calculator.

What Determines Your Calorie Requirements?

It’s not just about exercise. It’s about everything your body does from the most basic functions (keeping you alive) to high-performance strength training, to studying for an exam, to walking to your car.

It’s common to make the mistake of only thinking about how many calories you burn from exercise and nothing else.

And this a major mistake.

In fact, exercise, for most people is a small portion of your daily energy expenditure. While you might burn 250-300 calories during your hour-long gym session, you’re burning much more than that through the day during your regular activities.

So for those losing weight, you want to remember that it’s not just about exercise, but all of your daily activity that counts.

What you burn over an entire 24-hour period is made up of 3 variables

Those are:

- BMR (basal metabolic rate)

- NEAT (non-exercise activity thermogenesis)

- Exercise (weight training, sports, or cardio)

Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR), Resting Metabolic Rate, Body Composition

BMR is what you burn every day to keep your body functioning and alive.

Think of it like this… if you were to stay in bed all day doing nothing, your body would still require a certain amount of energy to function. This is known as your resting metabolic rate (basal metabolic rate).

We tend to equate our activities such as training, cardio, and general walking around as what burns calories, and what contributes to weight loss.

And while those activities do burn calories, our bodies are also burning calories just to stay alive. All of your organs require energy from food to function normally.

Your brain requires glucose (hello, sugar) for processing power. Your stomach requires calories to digest food, which it turns into useable energy for later.

Your heart requires energy to keep beating. Your skin and bones require energy to repair themselves from everyday cell turnover (cell replication).

Essentially, your body requires a certain number of calories daily to survive, and this is largely based on your body weight.

But weight loss, weight gain, and muscle gain require either a calorie deficit or calorie surplus, depending on your goal.

Therefore, your total caloric intake will change based on the goals.

Now we have to think about our activity…

Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis

(NEAT) is energy expended for everything we do that is not sleeping, eating or sports-like exercise. NEAT can differ wildly from person to person.

You might have two people who are seemingly identical in their daily routine, exercise intensity, muscular build, and eating habits but have differing levels of energy requirements.

Outside of some slight metabolic differences, the amount of food they need to maintain their weight will be most affected by their NEAT. And some people are generally more fidgety than others.

Some tap their foot during work, while others hardly move at all. Some find it incredibly hard to sit still, and others can be perfectly fine laying around on the couch all day.

NEAT can have a drastic impact on your energy expenditure when it doesn’t outright negatively impact your daily routine.

For instance, the person who bikes to work, or spends time getting up at regular intervals from their desk to stretch and move around, are going to burn more calories from these activities than someone who drives to work and is chained to their desk all day.

This is why people with active jobs (being on their feet all day, delivery routes, doing manual labor) can seem like bottomless pits when it comes to how much they can eat without gaining weight. And weight loss seems to come much easier to them than it does for people who are less active.

As you can see, someone’s maintenance calories will vary depending on what they’re doing most of the time. And the number of calories they consume is going to be dictated by their needs, goals, and health requirements (more on this below).

Now… deliberate exercise is what you do above and beyond your normal daily activities. Things like weight training, cardio, intervals, and sports — these are all voluntary activities we choose to do, and the amount of time spent doing them, plus the intensity in which they’re done at will affect your total daily energy expenditure.

Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE)

All three of these variables make up Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE). Your TDEE is your BMR plus all the other activity (NEAT and exercise included).

This includes moving around for daily tasks (getting out of bed, brushing your teeth, walking around your house, making food, going to work, training at the gym, playing frisbee in the park, and everything else you do).

All of that extra activity requires calories for energy. As a result, your total energy requirements go up. TDEE is also sometimes referred to as your maintenance calories, which makes sense given what I’ve laid out thus far.

Recap: BMR is what your body burns at rest. NEAT is all the activity that’s not exercise-related. BMR + NEAT + Exercise = TDEE, otherwise known as maintenance calories.

Weight Gain, Weight Loss, and Energy Expenditure

Regardless of your goal to increase lean body mass and gain weight, or to shed fat and start a weight loss plan, you have to first be able to calculate maintenance calories accurately and easily.

Sure, if you want to lose weight, you know you need to eat fewer calories, but how do you arrive at that number? Same thing goes for increasing your lean body mass… building muscle requires you eat above and beyond your maintenance daily energy expenditure requirements.

It can get confusing pretty quickly… especially if you think you already consume fewer calories than you actually are.

Most of the time, people are grossly unaware of their energy expenditure (number of calories they’re burning), and they don’t know where to start with figuring this out. This is why using a maintenance calorie calculator can be helpful.

To calculate maintenance calories, here’s a good starting point…

Equations For Maintenance Calories

For maintenance calorie equations, it always starts with the BMR.

Some popular BMR equations are known as the following (which are the names of the creators):

- Harris-Benedict Equation

- Mifflin St Jeor Equation

- Katch-McArdle Formula

For sake of simplicity, we’re going to use the Harris-Benedict Equation because let’s face it—each maintenance calorie calculator will give you similar numbers, and it’s not worth worrying about which one is most accurate.

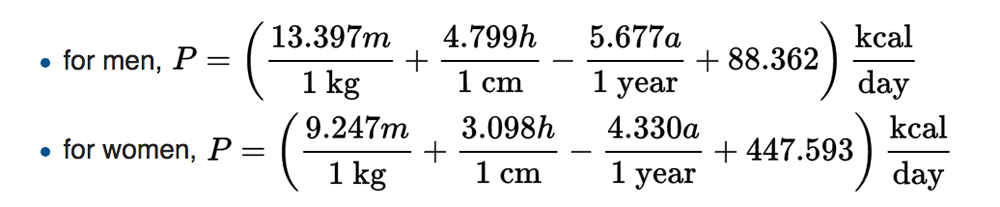

Here’s a quick snapshot of the math required for the Harris Benedict Equation:

Key for the formula above:

- P is total heat production at complete rest

- m is mass (kg)

- h is height (cm)

- a is age (years)

STOP: before you try to work out this equation on paper, or find a calculator online, don’t waste your time. I’ve created a maintenance intake calculator below.

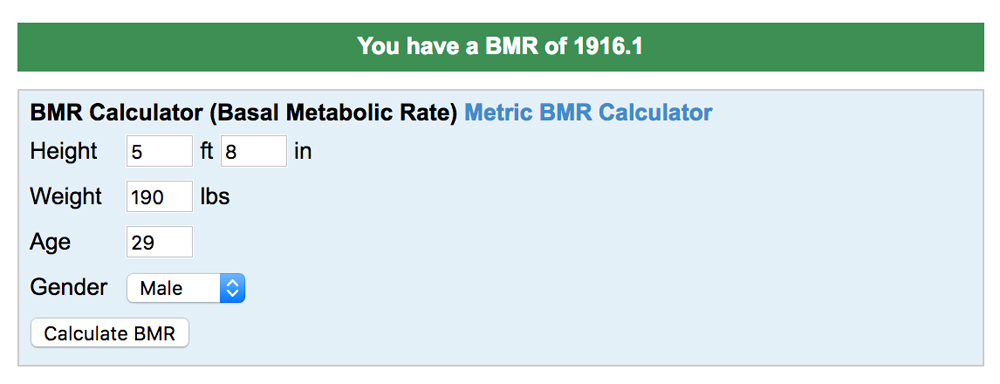

But for sake of example, let’s use a common BMR calculator to start with.

I entered the following data:

- Height: 5’8”

- Weight: 190lbs

- Age: 29

- Gender: male

Here are the results:

When we do some quick math, 1916 divided by 190 pounds is roughly equal to 10.

[1916 / 190 = 10.08]

So, a quick way to get your basal metabolic rate with simple math is to multiply your body weight by 10. And this leads me into the next section, which will be extra useful.

Maintenance Calculators & Activity Levels

If you’ve ever used a BMR calculator while trying to figure out your maintenance intake, they usually have multipliers for you to use.

And they tend to read something as follows…

In order to determine your maintenance calories, multiply your BMR by the number below:

- Sedentary (little to no exercise) | 1.2

- Light exercise (1-3 days of exercise per week) | 1.35

- Moderate exercise (4-5 days of exercise per week) | 1.5

- Intense exercise (6-7 days of exercise per week) | 1.6

- Hard exercise (marathon training or twice daily training sessions) | 1.75+

Depending on what resources you use, the language will vary somewhat, but how does this translate to real-world levels of activity?

Are you sedentary if you sit all day long? Hint: yes, you are.)

What if you do yoga a few times per week? Still sedentary or are you now in the light exercise category?

What if you weight train 3 days per week but have an office job? What now?

It can all get confusing, so I’m going to lay it all out for you here in easy-to-understand terms.

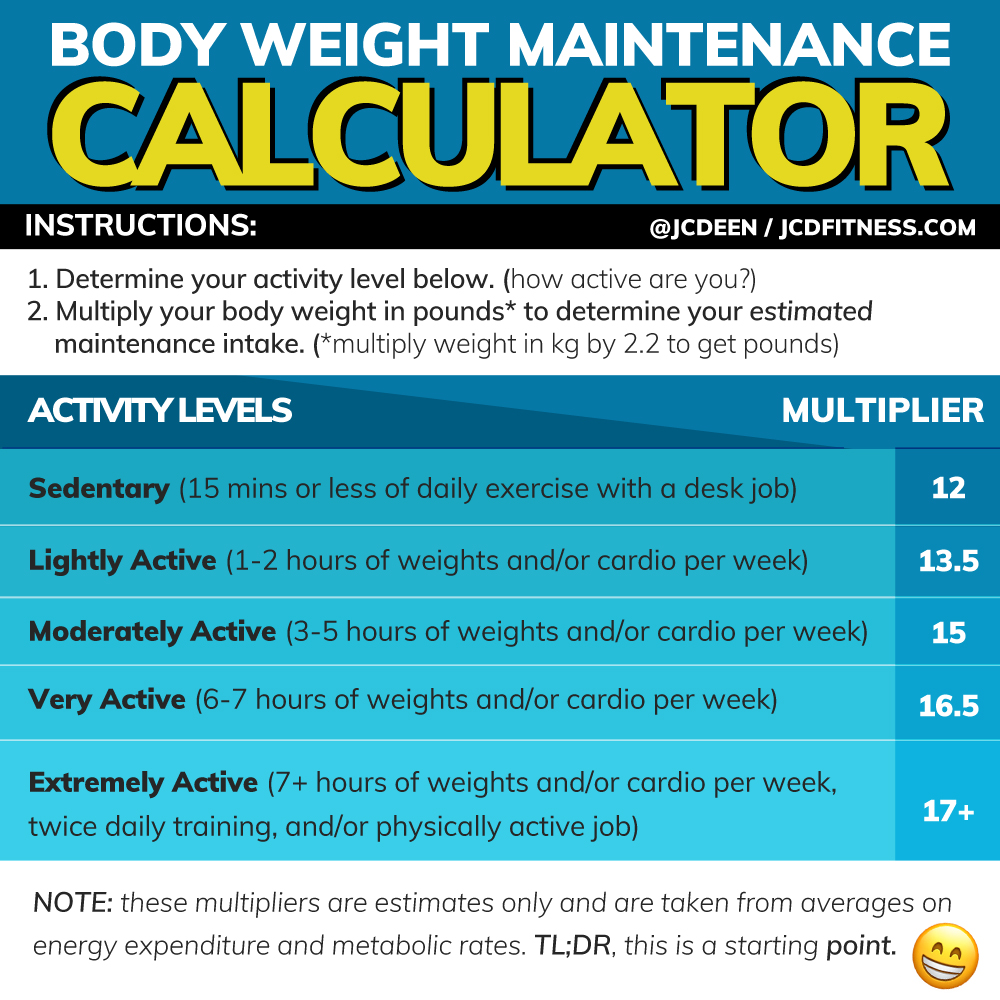

First, here’s a quick chart for easy reference:

Struggling With Weight Loss?

Learn My Tricks & Tips to Make Weight Loss Easier

(it’s actually quite simple, and I can help)

One thing I want you to keep in mind before I give you these multipliers is the following: MAINTENANCE CALCULATIONS ARE ONLY A BEST ESTIMATE.

And nothing more than that. It’s a starting point to help you get headed in the right direction.

So don’t get upset if the calculations (or the calculator below that I had made for you) are somewhat off based on what you know to be your caloric requirements from your own experience with tracking your nutrition and body weight or body fat percentage over time.

Here’s how you can calculate maintenance calories the manual way, without relying on a calculator.

Step 1: Determine the activity level from the figures below (taken from chart above)

- Sedentary: 15 minutes or less of daily exercise (anything goes) with a desk job | 12

- Lightly Active: 1-2 hours of weights and/or cardio exercise per week | 13.5

- Moderately Active: 3-5 hours of weights and/or cardio exercise per week | 15

- Very Active: 6-7 hours of weights and/or cardio exercise per week | 16.5

- Extremely Active: 7+ hours of weights and/or cardio exercise per week | 17+

Notes:

- Cardio includes anything from walking, running, biking, swimming, yoga, pilates, step aerobics, and the likes.

- If you have a rather strenuous job, such as construction, or mechanics, or something similar, then you’re likely going to require more calories for maintenance than laid out (hint: bump your calculation up a modifier)

Step 2: Multiply your bodyweight in pounds by the activity level modifier above (for metric conversions, take your weight in kilograms x 2.2).

Example: if you’re moderately active, you’d multiply your bodyweight in pounds by 15.

Step 3: Put this into practice and monitor your weight over two weeks. If you gain weight, then you know you’re eating above your maintenance intake needs. If you see some weight loss, then you’re eating below your maintenance intake needs.

Maintenance is an average over time, so it’s best to weigh yourself frequently, every day (or every other day) and take an average over 14 days.

The reason for this is because you’re not going to weigh the same every day and if you only weighed yourself twice over two weeks, it might look like you lost or gained weight when in fact you’ve maintained.

Example: On day one you weighed in at 190 pounds and day 14 you weighed in at 194 pounds. From those two measurements alone, you would assume you gained 4 pounds!

But if you weigh yourself daily, you might find that some days you weigh 188 and others you weigh 191.

On the day before you saw the 194, you happened to go to a barbecue and ate a bunch of wings and burgers. And all the sodium made you retain more water than normal, causing you to weigh a few extra pounds when you weighed in.

If you were aiming working on weight loss, you would be really discouraged if you saw a big spike on the scale.

One more note for accuracy: when weighing yourself, it’s best to do it under the same conditions every single day. I prefer to do it in the morning when I wake up right after I urinate, and before drinking or eating anything.

Struggling With Weight Loss?

Learn My Tricks & Tips to Make Weight Loss Easier

(it’s actually quite simple, and I can help)

Maintenance Without A Calculator

If you want to determine your maintenance calories without using fancy calculators or equations, the best thing to do is track your intake every day for 10-14 days and track your body weight over that time period.

If you gain weight, you’ll know you need to eat less. If you lose weight, you’ll need to eat more.

The main thing here is to be as accurate as possible with your tracking, so be sure to check out the following resources:

And finally… how many calories do you need? Here’s a calculator that does the work for you. 👇